“Yekaterina, work at your needlework!” Teacher Alina snapped. I was gazing out the window onto the bustling town of Podentsky, a mining metropolis in the thick of the Urals fifty miles from Yekaterinburg, my namesake. I watched copper-tinged snow fall. It was winter, 1910, and I was seventeen years old. The Popovas, our regents – we knew no tsar in the Copper Lands save Tsar Nikolai’s despicable Bailiff – graced our mountains with mineral and vegetative bounty, but everything here was tinged green as crabapple ice. Even the emerald snow.

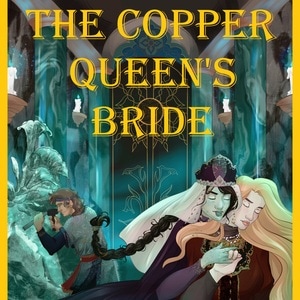

I giggled, braiding Azovka’s black hair. It had streaks of green and cinnamon striated like veins of ore throughout. She was my dearest friend.

“What a vision you are!” I crooned, ignoring Teacher Alina. I tugged lightly at Azovka’s hair and twirled it round my thumb. Azovka smiled, her malachite eyes and scaled legs shining in the oil lamplight. Teacher Alina trimmed the wick as Azovka practiced her algebra.

“Use the malachite hair tie,” Azovka whispered, smiling secretly. She drew a band of copper from her purse and enchanted it to be a ribbon as fine as the tsarina’s silk. You could find malachite like that – a gown – in sheets at Snake Hill. Azovka, the Mistress of Copper Mountain, liked to grow it like Japanese bonsai trees. She had whole gardens of gems, below the Urals in her Copper Mountain.

I ooohed and ahed as my classmates looked on in fear. The townsfolk treated the Popovas with awe and superstition. But Azovka was my friend – though immortal. I trusted the Copper Men in a way Prokovitch the Stonecutter did not. I confided in Azovka like our Landlord Peter swallowing dirt from Mokosh before striking a rent deal – a holy bond. The mining men, they said the Copper Women were their deaths. But to me, Azovka was life.

“Okay, Azovkalisha,” I cooed, my blonde hair and ruddy fat cheeks – I was plump as a partridge, with muscles from hunting and lifting heavy stones for father – shining in contrast to Azovka’s slim elegance. I tied the living stone around her hair. It was any day in Podentsky. It was all there would ever be.

We played P’yanitsa, what Americans called War, and our old playing cards had green crowned lizards on them with maiden’s faces and brown braids – the Popova family crest.

“Ha!” I said, triumphing over Azovka’s queen with my king of hearts. “I’ve stolen your heart, Azovkalisha.”

“It has always belonged to you, my bosom friend.” She said, then winked. “I’m hungry, Katya,” Azovka whispered, fingering her freshly plaited braid. The malachite ribbon snaked like her lizards around her copper-black tresses. We bundled up in our dresses, malachite belts, kerchiefs, elk boots and white fur coats and ate lunch down by the stone works. The grain mill churned in the river’d distance, and horses and buggies rode through the crossway, carrying iron, copper, malachite, semiprecious stones, and even the rare diamond or sapphire – all guarded by vila militias. Dedushka always warned me to stay away from the vila – the storm spirits would suck you dry.

Azovka’s nanny Rubenya, a crinkly Copper Woman, had made us white borscht. We ate it with some ham sandwiches Azovka had fixed. Azovka had spent all night with the dough – she really liked to bake. We dipped the rye bread in the soup from the thermos. Our mothers had both died in childbirth, and my father, Stepan Petrovich, was the captain of the Copper Guard, an ancient order of warrior miners that served the Popovas.

Alina and her father Alexei Popova needed minerals to survive – the finest Yakutian diamonds, jade from China, topaz from Brazil. The Copper Guard ran a vast network exporting the Ural Mountain’s riches past the Malachite Gates and importing minerals from abroad. They let the rest of the world in past their diamond swords. My dedushka was a quiet man, a man of action – I was the only talker.

“Here, Azovkalisha – I picked this one from the river,” I smiled, handing Azovka a tumbled moissanite.

Azovka’s eyes brimmed with tears. “Why are you so kind to me, my Katy?” she said fondly, taking a bite with her pearly teeth. They cut the gem like butter, and the lizards that always thronged by her feet thrummed with excitement. Azovka’s scales foiled. Her eyes turned black as she absorbed the mineral’s essence.

“Because, Prokovitch the Stonecutter said that someday, you will be my dearest treasure – more precious than malachite to the Copper Kingdom. And I always liked pretty girls – I am ugly, dearest Azovka! I need a polished best friend to harp up my strengths when it comes time for us to wed some awful, belching husband. Ah, dedushka has his eyes on the Landlord’s son: stinky, ugly Mikha. Blech!”

We skipped around her lizards, hand in hand, then fell down into the snow, laughing, and made green angels out of the cloudy powder. It cushioned our fur jackets. Azovka stuck out her tongue. “Not the pimply, doughy landlord’s son. I think you’d do well with a stonecutter like old Prokovitch.”

“Hey!” I smiled, pulling at her embroidered mittens. “He is 53!”

“A joke,” Azovka said, her peacock eyes brimming with mirth. “Promise me you will never leave me for a boy, Yekaterina.”

“I do.”

We swore on Mother Mokosh, the earth goddess’, skin, swallowing and spitting out some red clay, crossing our arms, and throwing her lizards into the air.

“May I have some food?” a willowy voice came. Azovka and I froze, caught in the act of sisterhood. It was a tall, gaunt boy, with a mop of dusty blonde hair – a beggar in tattered clothes. But he had soft blue eyes, and he reminded me of Ivan Tsarevich chasing a Firebird.

My heart dropped. He was the most beautiful creature, save Azovka, I had ever seen. “Sure,” I said, offering the beggar the rest of my rye and borscht.

Azovka smiled. “What is your name, stranger? I am princess of this town. Someday, I will become Queen of the Copper Mountain.”

The beggar hungrily tore into the bread. “That’s nice I guess.”

Azovka folded in on herself, blushing.

I tapped the boy gently on his elbow. “You should bow down, fool.”

“I am older than you. You look like childish maidens. I’m eighteen. Girls are the foolish ones.”

“You don’t look old,” I said.

“Whatever,” Azovka sighed. She made the lizards crawl up his legs. The boy just smiled and kissed one. “Weirdo,” Azovka replied.

“What’s your name, beggar?” I asked. I wanted to clip this stranger’s wings and keep him. Fatten him up with my blinis. Make him pierogis and borscht. Ask him to stay. Just like I had Azovka. They were both horribly broken. I wanted to fix them.

All I could do, though, was ask the wanderer’s name.

“Danilo,” he said. “Someday, I will be famous.”

Azovka smiled. “For what? Begging? I am already famous.”

“Spoiled, maybe,” Danilo said obtusely. “Look at the malachite on you.”

“I am the princess, I told you!”

He winked. “Titles don’t churn butter.” Danilo toyed with a lizard. “Things are changing beyond the Malachite Walls. Rasputin rides. I fled St. Petersburg to find a better life – rode the rails to here, last stop past Yekaterinburg. Outside the Malachite Walls, beyond the reach of the Copper Guard – no one even dares think what kind of magick lives in the Copper Kingdom, with the Copper Men. May I meet you two here for lunch tomorrow?”

Azovka and I shared a look and smiled. “Sure,” we said in unison.

He smiled back, a bright wound of red.

“Ask Prokovitch on Georgin Street for a place to stay. He’s in need of a shepherd. You look fit for that, beggar boy,” I said with all the love a seventeen-year-old girl could tease the object of her desires with. I liked the dirt on Danilo. I liked his dreaminess and odd charm.

Azovka just stared at her lizards. I liked that about her too.

And thus began the winter of our lives.

Comments (0)

See all