Assume the axiom of choice.

Take the interval from 0 to 1.

take any two numbers x, y from the interval.

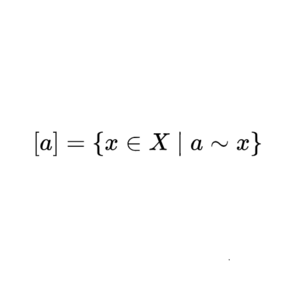

Apply the following filter. If x-y is a rational number, they go in the same bin, but if x-y is an irrational number, they go in different bins. This is an example of separating things into equivalence classes.

Rationals are extremely boring, and they all like to stay the same. A rational plus a rational equals a rational. They all hog the same bin.

Each irrational gets its own special unique bin. Take the irrational number π. It will always remain irrational when paired with a rational. π-1, π-2, π-3.14, π-3.1415, π-⅔. The rationals cannot dent the infinite complexity inherent within an irrational.

An irrational plus an irrational can be sorted into either of the two bins defined above. The proof for this is trivial and left as an exercise for the reader.

Assume a ruler.

Project the rational numbers onto the ruler. Do the same for any irrational number 𝕀 of your choosing. It should become obvious over time that the bin of any given 𝕀 is merely the rational bin shifted by the quantity of 𝕀. An infinitely many number of shifts, each more diagonal and as real as the last. The proof for this is trivial and is left as an exercise to the reader.

Assume a set S.

Assume ∀ bin (∃! a ∈ bin, a ∈ S_☾)

or,

Assume that:

S ∋ s_1,s_2,s_3…,

S_1 ∋ s_1+r_1,s_2+r_1,s_3+r_1…,

S_2 ∋ s_1+r_2,s_2+r_2,s_3+r_2…

S_3 ∋ s_1+r_3,s_2+r_3,s_3+r_3…

⋮

Since S contains each element of each bin exactly once, each variation of S is simply shifting the ruler we have projected S onto another, bigger ruler that measures it, by the quantity of each rational number r we have chosen for a specific set, with a one-to-one correspondence. Since both the rational numbers between the interval 0 to 1 and each set S_x is infinite, we can say that this goes on forever.

Since each S_x is shifted by a unique rational number, they are disjoint. Each number in each set does not appear in any other set. This will be lemma (1).

Since all the S subsets as a whole include a unique representative from each bin, augmented by each set's corresponding rational, the process of which goes on indefinitely, we can say that each number in the interval 0 to 1, rational or irrational, can be found in one (and only one) of the S_x. This will be lemma (2).

Since each S_x contains one, and only one element of each bin, each S_x has the same cardinality. This will be lemma (3)

Since all

∪S = S_1 ∪ S_2 ∪ S_3 ∪ S_4 …

|∪S_☾| = |S_1| ∪ |S_2| ∪ |S_3| ∪ |S_4| …

Because (2),

if S has a size,

1≤|∪S_☾ |≤3

Because (3),

|S_1| = |S_2| = |S_3| = |S_4| …

Which is equal to

|S| = |S| = |S| = |S| …

This will be lemma (4).

Because (1), and because S is an indefinite (read: infinite) series,

if S has a size,

|∪S_☾| = |S_1| + |S_2| + |S_3| + |S_4| …

Because (4),

|∪S_☾| = |S| + |S| + |S| + |S| …

Or, in layman’s terms,

|∪S_☾| is equal to S multiplied by itself an infinite amount of times.

{(1≤|∪S_☾ |≤3) ∩ (|∪S_☾| = |S| + |S| + |S| + |S| …)} is impossible.

Therefore, S_☾ has no size.

☽

Comments (0)

See all