I could sink into it every evening, the sullen breeze upon pulling aside the curtains, sitting to the comfort of microwave-heated dinner. The fact that I haven’t gone down to the dinner table for more than five minutes is again eminent. I was fine as long as I haven’t been persistently interrogated.

Or for as long as I don’t remind myself of the grisly quagmire I’ve walked into, and walked away from, I would immerse myself in perfunctory, tedious work. Not entirely that easy, it would come and poke at me, sinister and peering on my shoulder mad and Cheshire-like, tail curing and lashing. I could last days, weeks, without steadily turning demented enough to hurtle towards the window and break my bones.

My phone rang.

I hesitated, then placed it to my ear the way one fears of something frightful coming from the other line.

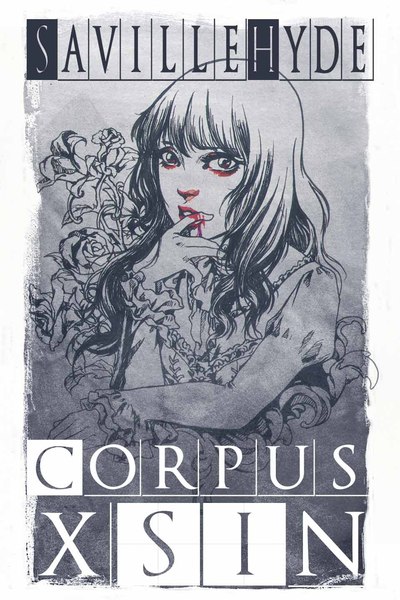

“Cal.” Sin’s silken voice, a single pleading tone in a placid evening.

I answered a distant “Yes?”

“It’s a full moon tonight.”

I looked out my window. The moon was surprisingly larger.

“I once saw the moon with blood in my hands. It pacified the sharp, crimson color. I thought my skin looked like china. You know what I thought?”

“What?”

The china cup in my mother’s cupboard, the ones I took out to play. One time I broke it, saw it shatter on the floor, fragments breaking apart. I got frightened. I gathered every piece then looked for some super glue. Piece by piece, I glued them together.”

I sighed, “Still, your mom got mad.”

“My mom was good at coping. She knew nothing can be undone. I always hated her for it. She looked at me like one of those paradoxically misplaced creatures among her children, then inspected the cup if I managed to glue all the pieces in. Then she placed it further back, behind the row of cups, a shunned, unsightly thing.”

Her voice faded. I lowered the phone, stared back at the window where the moon shone. I imagined she was alone, in a park or in a promenade, sitting with her hand against the moonlight, shoulders trembling and eyes brimmed with tears. “Did you know,” I said, placing the phone back against my ear, “Did you know that she didn’t cry for you?”

A lingering pause, then she replied, “Yes.”

I buried my face in my palm, just to shrug off how deeply hurt and defused I was to hear a heartbroken reply. “I’m sorry,” I managed to say.

She gave a small, dismal laugh, “But I’m glad that you remembered me.”

She hung up, the vacant bleeping resonated. I stood up, pried open my window and placed an ashtray on the windowpane. I have never stared at the moon with such dismal sentiment. I wondered if that would be every single case whenever the full moon paraded itself in the night sky. A kill, perhaps the first one, her mother in palpable resentment, her death in a whirring feature-film spectacle.

I could have said it. I didn’t entirely remember her. I refashioned a memory of her in a way it would suit my standards. Isn’t that what you usually do with the deceased?

Isn’t that what we always do?

Comments (0)

See all