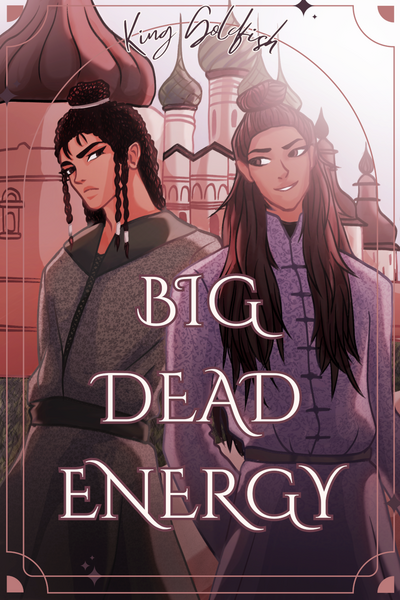

“Your cousin kept his word. He didn’t intend to incarcerate me,” Sanya said soothingly. “His people took me to a place in the city to keep me. Two guards stayed with me, but they rotated. Someone’s absence at the palace must have been noticed; someone must have been followed, because Knyaz Aksana’s guard found us and brought us back here—”

“Why didn’t you fight?”

He gave me a gently reproachful look and dropped my wrist. My fingers caught on the chain. “I would not fight your aunt’s guard while you are trying to make peace with your cousin.”

“They shouldn’t have put the manacles on you,” I muttered. I tugged on the chain with my index finger and he moved his hands back to his lap, massaging his left hand with his right. There was a webby purple pattern on his left hand. His grip had been cold even though it was a balmy spring day. His fingers were curled stiffly toward his palm.

“They didn’t at that time. They didn’t know I was a volshebnik. They took us to the prison in Whitecap Palace and asked who I was.”

“What did you say?”

“I did not answer that question.”

“Very wise.”

“I told them I was there at Semyon Aksanevich’s behest, and they could ask him any questions they had. That was that, until last night. Knyaz Aksana came to see me. She asked who I was. She asked if I was Aleksandr Artyomovich. I felt compelled to tell her that I was. She asked why I was allowing myself to be held in a prison that I could easily escape. I told her I was here at Semyon Aksanevich’s behest. She asked if I was here at your behest. I didn’t say anything. She told me she would open my stomach and feed me my own intestines. She put the manacles on me.”

“You shouldn’t have let her.”

“She, too, asked why I didn’t fight.”

“I’ll get them off. Semchik—oh, Tajna, Semchik! Your cousin—Filipp Artyomovich ambushed Semchik. We got away, but he sent me here and went back to help his men. We found Timofej Artyomovich’s foot and a letter with a Gorakino seal on it, but I don’t know what the letter said. We were bringing it to the codebreakers.”

“You found a…”

“Yes, a foot. But that’s not the important part. The important part is—”

“Filipp Artyomovich.” Sanya’s face darkened.

“Yes. I assume Semchik isn’t dead because he told Aksana I was coming, but if he’s not dead, then he’s…” I cut my eyes to the guards. Nestor and Agafya were standing with their backs to us, staring straight ahead at the opposite wall, but the nameless little shit who’d mistaken us for people he could exercise his little prick ego on kept glancing over his shoulder. I finally slid up on the bench next to Sanya and whispered in his ear, “He might have killed Filipp, and that would…”

“Yes,” Sanya said, not whispering at all. “I understand.”

“I’m sorry. I know he’s your—”

“I don’t care about Filipp Artyomovich,” he said. Then his brow furrowed. “It is… surprising, though. For what purpose was Filipp Artyomovich there?”

I kept whispering, one eye on the puffed-up guard. “He said he was there investigating, but I think he was there looking for Timofej Artymovich’s body, too, only he wanted to get rid of it. Well, and he was looking for me.”

He nodded, but his brow was still knotted, eyes staring past me at the back of the cell.

“What is it?”

“It’s strange. Filipp Artyomovich has never liked his brother.”

“What does liking have to do with it?” Then I thought to that day in the Sundered Lands when Sanya broke up the fight between him and Semchik. Filipp said he was going to be knyaz in Gorakino one day. “What, does he think if he gets Vasilij executed he’ll get to be knyaz instead?”

Sanya’s eyes shifted back to me. “Some people think that Vasilij Artyomovich looks like me.”

I frowned. “No, of course not. He’s terrible, and you’re—okay, when I first met him, I did think he looked a bit like you. Except for those eyes. And the nose.”

“He gets those from his mother,” Sanya said. He looked down at his hands, which were uncharacteristically fidgety. “His mother and my father were very close in the past.”

“I’m glad your father had a friend, I guess; Knyagina Ulyana seems like—but—wait a minute, do you—do you mean that Vasilij is not Knyaz Artyom’s son? Do you mean his father is…”

Sanya looked pained. “We would never say such a thing out loud. A minor cousin became intoxicated at dinner once and said something within earshot of Knyaz Artyom. Knyaz Artyom had him tried for treason. His execution was commuted, but Knyaz Artyom took his tongue. He loves Knyagina Ulyana very much. He loves Vasilij Artyomovich.”

“But Sanya, that would mean that Vasilij is—”

“No, it would not,” he said, suddenly gathering himself up and putting on a haughty air I hadn’t seen him don since we were children. I wanted to reach up and touch his face, the lines at the corners of his mouth, the new skin I hadn’t seen before. When he held himself like that, a perfect glacier, he looked—not younger, but ageless.

He saw me looking. “Sorry,” I muttered.

He sighed, and his shoulder relaxed into mine. “Vasilij Artyomovich is not my brother. But he may be my father’s son. Regardless of the truth of the matter, it’s enough that Filipp Artyomovich believes that he is.”

“Did you… Did you know this whole time? Even when you were living there.”

He shook his head. “I never would have believed it. I did not look too closely at things. Before Lena died. Before I heard what I heard.”

“Who told you?” I asked suddenly. “About Tsura funding the rebels? I never asked back then.”

“You asked,” he said. “I didn’t answer. No one told me. I overheard Vasilij Artyomovich speaking to someone about it in the library.”

“In the library?”

“Yes. I was there when they came in.”

“Were you in the library a lot, then?”

“Sometimes.” He gave me a sidelong look. “When I wanted to be left alone.”

“Couldn’t you be alone in your rooms?”

“When I wanted to be alone where no one would find me. You are not the only one who made a habit of barging into my rooms.”

“Okay, did Vasilij know you went to the library to be alone?”

“You think he wanted me to overhear.”

“How else would he convince you to help me learn how to use zhiva?”

Sanya’s muscles tightened and the chain between his fists clinked.

“We were his puppets,” I said. “What’s going on in Veliko now?”

He was still taut as a bowstring. “I don’t know. Southern Veliko is protected by stewards from the surrounding oblasts.”

“Including Khorizova?” I hissed in his ear.

A door closed down the hall, and I jumped.

Sanya put his stiff hand on my knee to keep me in place. “Stay calm.”

“If they try those manacles…”

Footsteps echoed down the hallway, and all the guards stood at attention.

“If I let them put those on me, I might as well be signing both of our death warrants. I am not going to sit here and let happen to you what happened—Semchik!”

Though the guards were lined up in front of the bars to block us from view, they could not block the top of Semchik’s head, wild curls escaping from his top knot.

I jumped up.

“You can step aside,” Semchik said.

The guards parted, and he stepped up to the bars.

My arms snaked through, and I hugged him. Squeezing him was like squeezing a barrel, complete with the iron cladding.

He groaned and patted me on the back.

“I’m so happy you’re okay,” I said, words muffled by his shoulder.

“I’m fine, but if you don’t let go of me, I can’t let you out.”

“Let me out?”

“If you and Aleksandr Artyomovich are happy here, far be it from me…”

I jumped back. “Please, by all means!”

Semchik put out his hand, and one of our guard dogs deposited a key in it. He looked down. “And the manacles.” Another, smaller key was added to his palm.

***

Released from the cell and the manacles though we may have been, Sanya and I were still not free to flit about the palace. We were not free to be seen about the palace.

Semchik made us trade clothes with Nestor and the nameless guard, and the look on old nameless’s face when he was told he had to put my stinky, bedraggled clothes on was almost payback enough. The guards’ uniforms were not particularly comfortable, but they came with hoods.

We flanked Semchik on the way to his rooms, and I resisted the urge to march theatrically. I couldn’t help my buoyant mood, even if Semchik and Sanya didn’t seem to share it.

I’d spent plenty of time irritating Semchik in his sitting room and bedroom, preventing him from reading or sleeping, but barely any at all in the third room in the suite. When he was little, it had been a playroom, I thought, but now it was set up like an office, a heavy wooden table in the middle and bookshelves on all sides.

Semchik sent a startled Oleg away before we came in—Oleg, at least, looked his age, and I might not have recognized him but for the fact that Semchik called him by name—so we had to close all the shutters ourselves.

We lit the candles and sat down at the table, and then that was it. We just sat. The air felt heavy. Oppressive. My collar was suddenly tight.

I opened my mouth to break the spell, but before I could say anything, I noticed the source: Semchik and Sanya, staring at each other. Semchik with something like open hostility, Sanya a kind of reflexive straightening mixed with confusion. He looked away first, to glance at me.

When he did, Semchik, apparently satisfied, cleared his throat. “The letter,” he said.

“Yes,” I said excitedly, leaning over the table and inserting myself between the two of them. “What was in the letter?”

“I don’t know,” Semchik said. “But we’ve gotten it to Avdotya Aksanevich, so she will have an answer for us as soon as possible. Yuliya Aksanevich has the boot, not that I know what she can do with it.”

“Okay, great, and I’m glad you’re okay. I’m really glad you’re okay, but what happened with Filipp Artyomovich?”

“Filipp Artyomovich was looking for you. He didn’t find you.”

“Did you kill him?”

“No.” He smiled the tiniest of smiles. “But I could have.”

“Filipp Artyomovich attacked a knyazhich in that knyazhich’s home country,” Sanya said, as though he hadn’t believed it when I told him. “Knyaz Artyom can’t countenance that. It is an act of warfare.”

Semchik’s face soured. “Knyaz Artyom would have countenanced it fine if Ratty had turned up Greshnyj Iyu.”

“What did you do with him? Did you bring him back here?” I said.

“No,” Sanya said.

Semchik shot him an irritated look. “No. Detaining his son is what Knyaz Artyom won’t countenance. Once I put a stop to the fight—told Ratty he could search the camp all he wanted—I sent him home.”

“You did what?” I nearly exploded.

“I shouldn’t be talking about this,” Semchik muttered, casting his eyes to the ceiling. “I really should just have you killed and your body burned.”

Sanya almost toppled his chair standing up, but I (still lying across the top of the table) grabbed his wrist. “He’s joking, Sanya.”

“He shouldn’t say it.”

“Why did you let him go, Semchik? We could have used him to get to Vasilij, we—”

“All we would’ve done is start a war that Khorizova cannot fight right now!” Semchik snapped, slamming his fist on the table. “Dammit, Iyu.”

Perhaps I should have given more consideration to Semchik’s clear distress, but I couldn’t help myself. My mind was turning a mile a minute. “You said you sent him home. Do you mean back to his camp or back to Gorakino?”

“I told him to get the fuck out of my country, but knowing him, he hasn’t gone far. He thinks he already owns every piece of land he sets foot on, just because his brother made powerful friends. I could do little to disabuse him of that notion. The lives of his men never meant much to him.”

“Good,” I said.

They both looked at me.

“It’s good because—I know that doesn’t make any sense, but it’s good if he’s still in Khorizova. We need to talk to him.”

Comments (7)

See all