For two days, Ezekiel managed to avoid his mother.

He ate breakfast late, knowing she rose at dawn. He skipped evening meals, claiming fatigue. When she sent for him to train, he begged off with a bruised wrist or a fever that didn’t exist. If she noticed and she always noticed she didn’t force the issue.

But Rue noticed. Rue always noticed.

“You’re walking around like a rabbit waiting to get caught,” he said flatly as they crossed the training yard. “Whatever’s bothering you, you should just talk to her.”

Ezekiel tightened his grip on the practice sword. “I’m fine.”

Rue gave him a look that said, No, you’re not, but said nothing more.

Edric arrived that morning full of energy, laughing as he tossed a wooden blade to Ezekiel. “Come on, little tiger! If you’re going to carry a Bonaventura name, you need arms strong enough to use it.”

The drills were brutal parries, strikes, footwork over and over until Ezekiel’s lungs burned and his arms felt like lead. But Edric made it bearable, shouting encouragement instead of cold commands.

When they finally took a break under the shade of the training yard awning, Ezekiel blurted the question before he could stop himself.

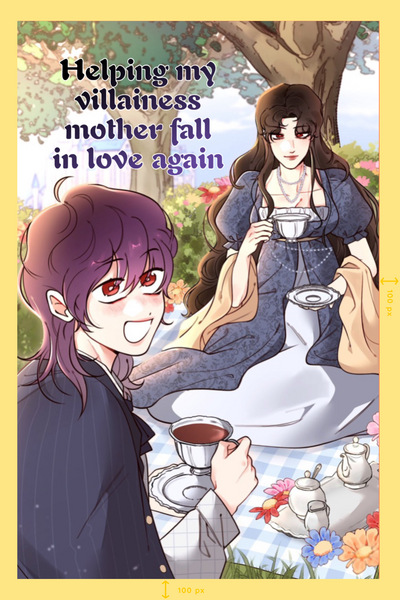

“Uncle Edric… there’s a painting. In one of the galleries. Of Mother and Father… sitting in a flower field. They look… happy.”

Edric blinked, then smiled faintly, wiping sweat from his brow. “Ah. So you found it.”

“Did someone else paint it?” Ezekiel asked hesitantly. “Or…?”

Edric shook his head. “No. They painted it together. Took turns with the brush, fighting over the colors like children. Lana said Ermes was terrible at painting flowers, but she kept every blotch of color he put down anyway.”

Ezekiel tried to imagine it: his cold, unreadable mother arguing over paint with a man whose smile lit his whole face.

“Your father used to say a painting wasn’t finished until your hands matched the canvas,” Edric added with a grin. “By the end of that one, they were both covered in pink and blue. Father scolded Lana for days.”

Ezekiel laughed softly despite himself. Then the memory of the cellar returned — the flash of steel, the boy’s body falling, his mother’s voice whispering

I love my son more than life itself. For him, I’d kill a hundred like you.

The laughter died in his throat.

Edric tilted his head. “What’s wrong?”

“Nothing,” Ezekiel said quickly, looking away.

That evening, Ezekiel ate dinner alone again. He told the servants to say he’d gone to bed early. But when he passed the main hall on his way upstairs, he caught sight of Lanastha seated at the long table, alone, staring at a glass of wine she hadn’t touched.

For a moment, Ezekiel thought she looked tired not the poised witch of Bonaventura, but simply… a woman.

He ducked away before she saw him.

Comments (0)

See all